Susan Chen: On Longing

at Meredith Rosen Gallery through September 26, 2020

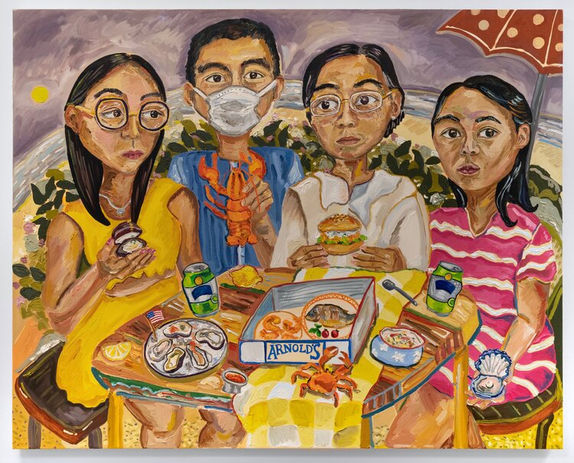

Susan Chen, an MFA candidate at Columbia University, NY, demonstrates her ability to document present Asian life, in New York City in this exhibition featuring a series of portraits about the Asian American diaspora and several paintings made from the artist's living room since the COVID-19 pandemic. Chen’s paintings are sometimes cartoon-like and suggest the informal portraits of Alice Neel.

For some time, the Asian-American segment of our population has been assigned the margins in art, but the situation is changing. We have the famous example of Maya Lin, whose outdoor environments and public art are renowned; also, the artist Paul Chan, well established in American avant-garde circles, comes to mind as an example of prominence in our current art world. So, Chen is not necessarily alone. Her work, though, addresses a younger generation, well-educated and ambitious, that is making its way up the ranks. The oils in the show are almost entirely on canvas, mostly express her personal life; many of the paintings seem to be portraits of friends. Brightly colored and expressively rendered, the work reflects the yearnings of the artist, whose exhibition is titled “On Longing.”

The paintings are not informed by theory or politicized identity so much as they represent a gifted young artist living in New York, whose intelligentsia has included Asian artists for some time--one thinks quickly of Noguchi. The new generation that Chen is depicting aligns just as easily with American culture as the foreign countries many Asian-Americans originally come from. It is a hybrid culture, in which allegiances become complex, and part of the strength of this show, and perhaps the reason why it has the title it does, results from the psychic intricacies of more than one affiliation. At the same time, there is considerable social confidence in the painting--one of the works, “Yang Gang” (2019), shows seven supporters of former presidential candidate Andrew Yang outside on the street, standing by a table devoted to political materials. Dressed for cool weather, the group is composed of individuals of various ethnic and racial backgrounds, thus forming a tribute to the city’s disparate populations. Radio City Hall forms the backdrop of the painting, situating the small assembly precisely within New York’s midtown.

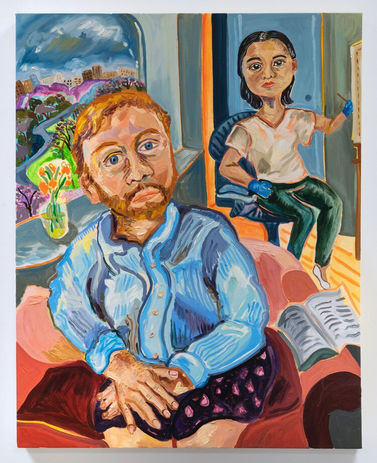

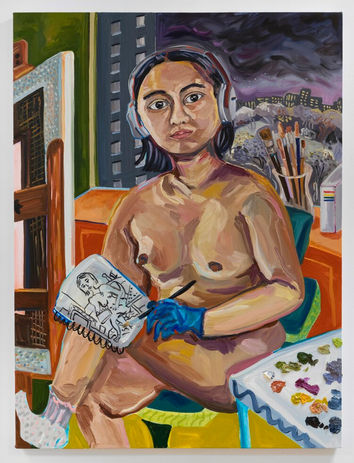

“Nude Self-Portrait” (2020) shows the artist clad only in socks, wearing headphones and sitting with a notebook whose open page shows an image that comes close to duplicating the painting itself. She also wears a blue painting glove that holds a brush, with a palette on the lower right and the edge of a wooden easel and canvas visible on the left (presumably the site of the composition we see). Dark clouds, closing in on night, along with buildings with lit interiors are seen through the window behind the naked artist, while on the ledge in front of the window we look at a glass container of brushes. This is art about art, and art about the artist, whose nudity projects direct description rather than overt sexuality. Another self-portrait, “Street Cars of Desire” (2020), shows the artist reading a book titled “How to Be an Artist”, sitting on a pink rug. In front of her is a glass bottle of flowers, along with three books; one is prominently titled “Portraits”. In the beginnings of the foreground we see a colored series of toy boxcars on a track, while in back of the artist, through a window, her viewers come across a rise with hills behind it, on top of which the rectangular boxcars again occur, with a sign directing them toward “Glory.” Clearly, the artist is calling out her ambitions as a painter; this may be a touch too self-aware, but all artists are prodigals when they are youthful.

Chen excels at her slightly rough, multihued portraits. Tadashi MItsui, the Japanese-born actor, is shown in a Hawaiian shirt, giving the artist the chance to work out colorful patterns. He sits with the wide eyes Chen usually gives her subjects; his handsome face is framed by silvered hair. Behind him is a painted winter scene: trees covered in white, standing on a semi-circle of white, presumably snow, with a deep mauve upper background. The painting is a likeness of a man of distinction. “Tenzin and Her Cactus Garden” (2020) shows an Asian woman with shoulder-length hair, one eye slightly higher than the other, sitting on a brown chair. Behind her is a panoply of green cactuses and decorative stones placed on sand. Other notes of color include the figure’s red and yellow scarves, as well as the deep blue of her blue jeans. The setting of an Asian person with a cactus garden enables Chen to paint a domestic scene, one equally devoted to her humanity and the bit of nature arranged in back of her. The artist is entirely sympathetic to both the human vulnerability and social reality resulting from her portraits of other Asians, which convey an atmosphere of inclusion and not a life alienated from the American present.

The first line of Chen’s website, “I paint in search for the meaning of home,” says a lot about the artist, who grew up in Hong Kong, was educated in a boarding school in England, and who then moved to the States to study at Brown before beginning graduate school in New York. The exhibition’s title tells us that longing is likely an ongoing consequence of her several moves; perhaps she is looking to a time when she will no longer be jumping from home to home. It may be that this is why her friends and acquaintances play so prominent a role in her paintings. When we are living in a time of massive emigrations, which include both the well-to-do and the poor, Chen’s paintings make sense as documents of a new era. Immigrant artists have often made their way to New York since the last century; Chen is no exception. In her portraits, of herself and those she knows, Chen establishes the visual context for artistic people who have come from all over the world to avail themselves of American culture, New York’s in particular. Her art acts as a translation between settings and cultures, while the visual aspect of the work relates most clearly to figuration done in recent generations in the United States. Even so, the implications, and visibly high ambition, of the artist’s paintings argue for the individualism characteristic of good contemporary art all over the world. We can hope that the artist’s longing and solitude will continue to be transformed into the empathic, colorful works she is now showing.

Jonathan Goodman