Yanzi Zhang: At the Crossroads of Art and Healing

Yanzi Zhang is a mid-career artist teaching in the Central Academy of Fine Arts' experimental art department in Beijing--this despite the fact that she studied traditional painting while a graduate student there. She is a painter of intrepid innovation, mixing her childhood experience--her father was a veterinarian, her mother a devout buddhist--with the events of a life lived late in the 20th century and early in the 21st. Much of her work concerns the implements of medicine--test tubes, medicines, cotton, gauze, acupuncture needles--some of it testifies to a spiritual yearning inherited from family. In the answers to my questions in this interview, Zhang looks to metaphysical suffering as the condition needed to assuage by art. This means that her search incorporates painting not only as a vehicle demonstrative of beauty, it also uses her classical background and unusual skill to address the common suffering that is our lot.

Indeed, while of course the artist acknowledges her Asian background, that is not a truly primary concern. Instead, it is the ubiquity of misfortune that is Zhang’s theme. Like any artist taken with genuine compassion, Zhang wants to heal--across cultures, across time. She is now spending more time in America, where her daughter, Cai Shen is studying in New York, and she is open to American influences that she might internalize while staying in New

York. Zhang looks toward diminishing the psychic pain that accompanies life everywhere--a buddhist truth that she may not follow in a conventional sense but which supports the heartfelt, regularly implied emotion in her art. We cannot ask for more from a contemporary artist; by being herself, she has become a painter with worldwide interests.

Science and Healing: An Interview between Jonathan Goodman and Yanzi Zhang

Goodman: Please indicate where you were born and educated before coming to CAFA in Beijing. At what point did you know you wanted to be an artist? Does art run in your family--did either of your parents practice art?

Zhang: I was born in Zhenjiang, Jiangsu Province, in China. It is actually a city with a rich cultural heritage as quite a few literati of ancient dynasties were born and lived here. I have loved painting since I was a child, and my enlightened education came from my father. My father’s family was a large local lumber merchant with a profound history. All of my father’s siblings, six in total, were well educated, and they were good at calligraphy, painting, or music. My father worked as a veterinary, he was one of the earliest bachelor’s degree holders in China and he graduated from Nanjing College of Agriculture.

I started to learn painting in an art school in Zhenjiang once I finished my junior middle school, and after that I studied at the Department of Fine Arts of a normal college. Later, I went to pursue my postgraduate study in the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. I majored in ink painting. I did not want to become an artist at the very beginning of my life and education-- I simply have loved painting since I was a child. If I retrospect now, the “art” that I have been worked on now is completely different from the “art” that I started to learn. My love for painting at first was almost an instinct, and the process brought me infinite happiness. But currently, in addition to the impulse to express, “art” further encourages me to think from a particular and profound perspective. What art has brought to me is no longer pure joy, but a project that I choose to confront with pain/brokenness and I manage to reconstruct. Therefore, my working status is becoming calmer and calmer and I prefer to be away from the noise. Even though I have embarked on this path and pursue a remedy for my interests, I don’t how far I will go.

Goodman: You studied traditional painting at CAFA, but now you are in the experimental art department there. How did so major a change take place?

Zhang: My course at the School of Experimental Art is “Conversion of Traditional Languages.” Although my major was traditional Chinese painting, I have not been constrained by traditions in my creations over the past decade. Instead I chose to confront them to express my inner voice. Additionally, I take it as my driving force and develop my unique individualistic expression. I have introduced my personal experience into my art, but it is also instructive for students. In my teaching process, I hope to make my research on “Conversion between the Tradition and Contemporary” more systematic.

Goodman: Does teaching at CAFA affect your own work in any way? Should experimental art be taught at a university, or should it be practiced outside of school because its values are so different from traditional art values?

Zhang: No, teaching does not affect my creation. I also serve as the Editor-in-chief of CAFA ART INFO. These work have endowed me with a broader vision. Ideas matter more than time for artists. Any category of art should have an experimental spirit. Every discipline in colleges should experiment. Only with the continuous integration of new ideas, concepts, techniques, art can develop and present something of this epoch.

It is open to question whether it is necessary to build a special school of experimental art. However, the Central Academy of Fine Arts specifically set up a school of experimental art with an intention to create a more avant-garde/free, unburdened environment than other traditional art colleges, where teachers and students can test the limits and boundaries of artistic creations.

Goodman: You are traveling a lot to America now, to see your daughter Cai shen, now a graduate student in art school in New York. How has American art and culture affected your outlook and your own art?

Zhang: My outlook is not yet formed, given the short time I have visited, but American art and culture, as well as scenery and humanities, surely enrich my knowledge. I often go to various exhibitions and performances here and I have felt quite a lot. Besides, the passers-by who wear headphones, walked hurriedly and keep talking to the phones, are also another kind of scenery; many streets are filled with the smell of marijuana; talks with artists, critics are also very interesting...These effects are subtle, and it will take time for me to internalize them.

Goodman: Your recent solo show in Edinburgh, Scotland, was titled "A Quest for Healing." What is the meaning of the title? Do you mean physical healing or metaphysical healing?

Zhang: “Healing,” a cultural concept, does not only refer to the treatment of physical illness. We know that if the body exists in a balanced and coordinated circulation, there will be no illness. Society, country, and nature follow the same principle. Lao-tse said that “the governance of a grand country is like cooking a delicacy.” The Confucian school aspires to “rectifying the mind, regulating the family, country and the world.” Both of them indicate the importance of “governance,.” Art, as a social and cultural existence, is an exact form and way of “governance.”

Goodman: Much of your art concerns medical matters: test tubes, medicine capsules, gauze and acupuncture. Why?

Zhang: My father was a veterinarian, and I had many medical instruments, including needles, tweezers, stethoscopes, etc., in my home since I was young. There were my childhood toys.

I never feel these are horrible and painful.

Everyone will be confronted with a lot of pain beginning with his or her birth, but pain means living. Even so, we are quite afraid of pain, and we always want to find remedy to cure pain. The physical discomfort may be cured through the pain of injections or surgery. How can the injuries, the psychological injuries one experiences in society, be cured? Does the pain need another, more painful treatment to be relieved? Is killing pain achieved by more pain?

Is there any real happiness? Do people need happiness or numbness? We were taught to be a “useful” person since we were young, what is the relation between “action” and “non-action”? These are the things I think about.

Goodman: What is the meaning of the numerous heads with the haloes in your installation? Are you referring to Buddhist spirits?

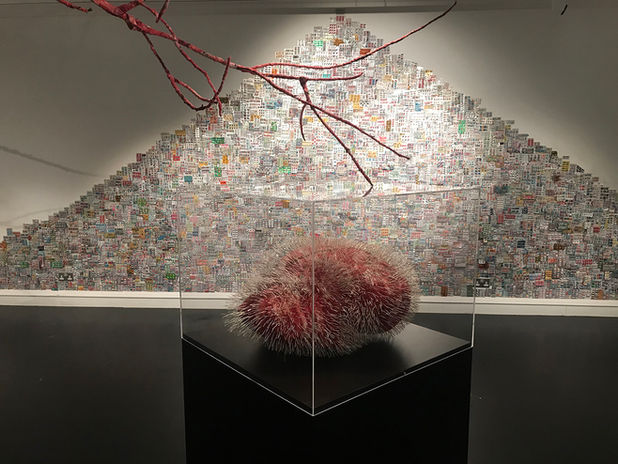

Zhang: When I made that work, The Remedy, in 2013, I painted thousands of Buddha statues, from the bottom of my heart. I had the idea of dedicating the painting to my mother. She was a devout Buddhist and she passed away.

In actuality, The Remedy (here meant to be an analgesic plaster) is a traditional Chinese medicine patch. If one has painful joints, the application of this plaster will be very effective and can relieve pain. I have painted lots of Buddha statues on these analgesic materials, which represent the spiritual conversion of many Chinese people.

Goodman: What does the text mean that is written on the face of the man looking at us in Secret Path (2018)? What role does the text play in the experience of the artwork?

Zhang: The text on the face are acupuncture points. There are many acupuncture points in traditional Chinese medicine. They cannot be seen during anatomy studies (on the body’s surface), but when acupuncture is managed, they do have curative effects.

In this artwork, I want to express that what is invisible does not prove that it does not exist. Is there a “secret way” for human beings to go to another world?

(Note: The artworks discussed above are inspired by Zhang Yanzi’s residence at the Surgeons’ Hall Museum in Edinburgh in the summer of 2017. Visiting the library adjacent to the museum, she was struck by “Notes in anatomy taken from lectures by Professor Turner, Session 1881-82” by David Middleton Greig (1864-1936). In this notebook, images of arteries are beautifully drawn and meticulously annotated. In Secret Path, Zhang Yanzi responds by linking the notebook to western and eastern medicine, and uniting art and medical science.

Each of the artworks are made up of two layers. Firstly, using the traditional Chinese medium of ink on paper, she painted a mountainous landscape in ink; adding colour to the landscape are red trees, similar to the shape of the arteries in David Greig’s notebook. The trees give life to the scene, just as the internal carotid artery brings life to the brain.

For the second layer, Zhang Yanzi painted a human face on silk which is placed atop the paper. These faces are modeled after illustrations from a Song Dynasty text describing methodologies of Chinese face reading. Face reading is a discipline still practiced as a tool for diagnosis in Chinese traditional medicine today. Ink dots show where the presence of moles might divulge clues to character or destiny. Within these paintings, one female and three male, each part of the face has a story to tell.)

Goodman: The figure in Sanctuary (2018) looks like a funeral piece. Is this true? What do you think that it symbolizes?

Zhang: This work was based on the earliest delivery bed used by Western doctors in Hong Kong, included in the collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences. With this delivery bed that constantly nurtures life, I want to pay my homage to the pain of women’s production, to the hope for life birth represents.

Life is born from a black hole.

(Note: Sanctuary and Scar are replicas of the shape of a surgical bed which was in use in Hong Kong until the 1960s, and is now in the collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences [HKMMS]. Affixed to the wooden frame of this artwork are analgesic plasters, illustrated by the artist with plants from the HKMMS’ herbal garden. The garden occupies an area of about 200 square metres on the grounds of the Old Pathological Institute in which the HKMMS is housed, and includes many plants with medical and healing properties in Chinese medicine. The garden includes a sculpture of Alexandre Yersin, whose discovery of the bacillus that caused the plague which raged in Hong Kong beginning in 1894 saved many lives.)

Goodman: Most of your work concerns spirituality and medicine--is it possible to connect the two in Chinese cultural traditions?

Zhang: In traditional Chinese culture, art is spiritual; landscape, flowers, and birds are symbolic. Ji Kang expressed a great truth in his Music is Irrelevant to Grief or Joy: “Mind and voice are different. Sorrow hidden in a sad mind, will be triggered when it meets music.” My art is not about medicine, but about my heart; thus, medicine is just a metaphor I borrow.

Goodman: Does your work fit into a specifically Chinese tradition--or do you consider yourself part of an international postmodern art population? It may be that China's culture is so old and very different from other cultures, it is difficult to remove yourself from its context, especially as a contemporary artist. Does this situation isolate you or not?

Zhang: I always feel like an outsider. I do not belong to any Chinese tradition, because I am a contemporary artist. If I have been put into any art group, it is because I was categorized by others.

Chinese and Western cultures are deeply different; however, I do not only absorb traditional Chinese culture; I have also absorbed Western cultures. This kind of mixture has made me unusual. I have the sense of isolation, just in America, it’s the same when I stay in China. Perhaps, people always feel isolated.

Goodman: What do you want to do in the next five years?

Zhang: I will keep expressing myself, and I do not want to cater to anyone. Since art is what I have been working on, I would like to see what I will find when I reach the end, and what I have done before it ends.

(Translation of Ms. Zhang’s Chinese interview responses by, Ms. Sue Wang, Central Academy of Fine Art, in Beijing.)