Ydessa Hendeles: The Milliner’s Daughter | The Power Plant, Toronto

By: Miklos Legrady

The academy says the question is no longer whether a curator is an author, but, rather, what kind of author(1) - how the curator answers or challenges the tempo, the contempo, the contemporary. If we’re not excited, then the work’s no good. This is the tale of a curator-turned-artist at a time when humanist values return to the white cube. Inside that curatorial box, feelings and sensations have started to interface with the traditional intellectual references. We might point and ask a question, but our feelings call the shots; colors affect emotions; light or shading tell a tale, a language of sensations is as complex as any language of words.

The Milliner’s Daughter at The Power Plant can be described in a language of emotions. Ydessa Hendeles’s work resonates even on Google Images; we call it chords of curiosity. But Emily Carr said it best; “Oh, God, what have I seen? Where have I been? Something has spoken to the very soul of me, wonderful, mighty, not of this world. Chords way down in my being have been touched. Dumb notes have struck chords of wonderful tone”.(2)

Science explains how art affects emotions and feelings, how the psychology of art enriches the soul. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio’s study of nonverbal language, such as Hendeles’s work, says that: “every perceptual experience is accompanied by emotional coloration—an evaluation of subtle shades of good or bad, painful or pleasurable, a spectrum of cognitive and emotional memories, providing an instant valuation… art is not mere ‘cheesecake’ for the mind. It is instead a cultural adaptation of great significance.”(3)

On that note, Hendeles plays this installation like a virtuoso on a violin; any single room held a tone, but together they made a small symphony. This exegesis may sound bubbly, but there’s no feedbag here; everyone in that space was captivated as the artwork yielded glimpses of its narrative.

Photos Miklos Legrady

Let’s use words like “cultured” to describe the tall statues as if from ancient Assyria, or the life-sized lady in a bell jar. In other rooms, wooden idols sit like ancient gods, polished over decades by thousands of childlike believers. They’re wooden artists’ manikins from 1520 to 1930—hundreds of them from tiny to life-sized - and they’re spooky. There’s a child’s working bicycle bell that is more than 30 times larger than life. We feel scaled down as if by that Alice in Wonderland pill that made you small, surprised by the humongous reading glasses on a gigantigerish book, Puss in Boots, whose large pages are reproduced as etchings on the wall. Feelings hover between velvet twilight and evening prayers, wooden lights and silver floors down the rabbit hole.

What is there besides the intellect? What qualities does art have to which thinking cannot do justice? Albert Mehrabian, born in 1939 to an Armenian family in Iran and currently Professor Emeritus of Psychology, UCLA, is known for his publications on the relative importance of verbal and nonverbal messaging. His findings on inconsistent messages of feelings and attitudes, often misquoted and misinterpreted in seminars on human communication worldwide, have also become known as the 7%-38%-55% Rule (4) to capture the relative impact of words, tone of voice, and body language in speech. This gives an idea of the relative importance of visual language, the precursor to written language and at least its equal in complexity of expression. A picture is worth a thousand words.

In From her wooden sleep…, Hendeles paints with manikins instead of pigment. They’re sitting in pews, hand-sized to life-sized, like Emperor Qin’s Terracotta Army. These serious wooden churchgoers in their polished pews awaken early childhood memories of when very big parents dragged very little us to religion, where solemnity occurred. It occurs consistently on both floors of The Power Plant, and this complexity attests to the artist’s inner light. Hendeles sliced a moment in time to draw a slice of art; she intersects some laws of nature to define art’s nature. It’s haunting—as haunting as the title, THE BIRD THAT MADE THE BREEZE TO BLOW, which gives me shivers. A Murray Whyte review in The Toronto Star mentions that Hendeles was still tweaking the show at the last minute before opening, which is so cute; it shows a real love of art.

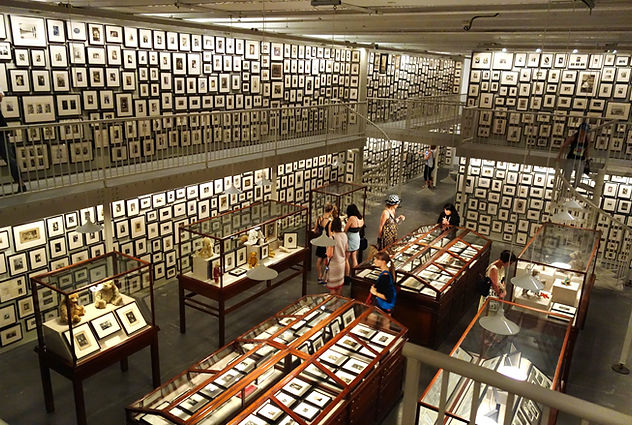

Katie Rider writes in The New Yorker of an earlier series, Partners (The Teddy Bear Project), made of images Hendeles found on eBay between 1999 and 2001. They’re drawn from personal collections and family albums, and sorted into groups according to subject, posture, setting, and numerous other taxonomic criteria—creating, according to the artist, 122 “typologies” in all. These include categories as unexpected as early 20th-century women’s basketball teams posing with teddy bears, wedding parties with teddy bears, nude women with teddy bears, soldiers with teddy bears, portraits of seated dogs with teddy bears, humans dressed as teddy bears, bears treated as teddy bears, and so on. (5)

Ydessa’s methodology is not much different from the rocks and earth used by Robert Smithson in Spiral Jetty. In both cases, materials are assembled to make a statement, except that with Hendeles the individual parts are signifiers with their own narratives, and the collected exhibition itself is the actual body of work. Consider that you walk inside this project as if inside Yayoi Kusama’s Mirror Room, but here you’re inside a book, inside the sculpture that surrounds you, inside a painting. Each small framed picture is a brushstroke in a larger work, just as the manikins are brushstrokes in The Milliner’s Daughter.

The curatorial foundation is obvious, but it’s now a template, a skeleton fleshed out by an artist’s vision. Hendeles spoke of the artist-curator interface in her 2009 doctoral thesis, “Curatorial Compositions”, for the Universiteit van Amsterdam. “Partners proposes an innovation in curatorial methodology in that it is a ‘curatorial composition,’ one that has its own unity and point of view, like an individual work in any artistic medium.”(6)

Endnotes:

1- Rui Mateus Amaral, The Author-Curator as Autoethnographer, MFA thesis, OCADU 2015 http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/273/1/Amaral_Rui_2015_MFA_CRCP_THESIS.pdf

2- Emily Carr, Hundreds and Thousands, Toronto: Clarke, Irwin & Company Limited, 1966, p. 6

3- Michelle Marder Kamhi, Why Discarding the Concept of "Fine Art" Has Been a Grave Error http://www.aristos.org/aris-17/discardingfineart.htm

4- Albert Mehrabian https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Mehrabian

5- Katie Rider, A Piercing View of the Twentieth Century, Through the Eyes of the Teddy Bear, The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/a-piercing-view-of-the-twentieth-century-through-the-eyes-of-the-teddy-bear

6- Ydessa Hendeles, CURATORIAL COMPOSITIONS, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2009 https://curatorialstudioseminar.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/hendeles_curatorialcomposition-unlocked.pdf

Photo Loring Knoblauch

Photo Miklos Legrady

MIKLOS LEGRADY: This seems a good place for an interview. Ydessa, I’d like to ask about your experiences first as curator and then as artist. Your work stretches definitions but the highest expression of a human soul does come from singing one’s own song. What was the impulse that moved you from supervising the playground to getting your own hands muddy?

YDESSA HENDELES: You could say my practice has its origins with The Ydessa Gallery, which I opened in Toronto in 1980 to focus exclusively on Canadian artists. I made a living as a galerist, although Toronto at that time was hardly a centre for contemporary art and it became increasingly difficult to keep artists happy and not lose them to European galleries. In 1987, my father died, which gave me the means to shift focus from a commercial to a more-philanthropic enterprise. I closed the Gallery and turned my attention to the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, which was the first privately funded contemporary-art exhibition space in Canada. For the next quarter century, I conceived and mounted more than three dozen shows at the Foundation, right up to 2012, when my mother died. The Foundation is still active, of course, but since then I have pursued my practice at the invitation of other galleries and institutions.

Over the course of my practice as a curator, I developed the idea of the exhibition as a “curatorial composition” and later adapted that to create and include my own artworks in the shows. That process has evolved especially since 2003, leading to my first show at a commercial gallery—Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York in 2011—and then my debut solo show, at König Galerie in Berlin in 2012. In retrospect, it seems like a natural evolution—from galerist to curator to making my own works. I did not consciously set out to be an artist. But I was repeatedly approached to make exhibitions—by the Marburger Kunstverein in the town of my birth, for example, and by Andrea Rosen, Johann König and Philip Larratt-Smith and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London—and I responded with site-specific projects. By the time I created From her wooden sleep… for ICA, my work was straddling curating and creating; it was both a curatorial project and an artwork. As I said, I did not consciously set out to be an artist, but the way in which I work is beyond curating. My work does not fit comfortably in any conventional categories, though it has been presented by institutions as something to be approached and appreciated as a work of art.

ML: In her seminal Against Interpretation, Susan Sontag warned of a hypertrophy of the intellect over sensual capability that she calls the intellectual’s revenge on the artist. Ydessa your degrees speak of studies over decades, which obviously hasn’t harmed your creativity, yet for others intellect has been seen to block instinct and the creative. How has that worked for you?

YH: Well, I don’t see that there is necessarily any conflict between intellect and what you call “sensual capability,” which might be better seen as complementary impulses. Which said, I tend to think more in images, which makes it hard sometimes to articulate in words what, as a creator, I intuitively feel is right.

I think my exhibitions are the natural outcome of following an artistic process that is practice- rather than theory-based. I do not use or make artworks to illustrate a trend or theme. I do not start out from an idea and then exclude works that don’t fit into it. Indeed, a core principle of my practice is that the exhibition space is key to the development of each exhibition. I always start from the context for an exhibition, which is analogous to an artist making a site-specific work.

My goal is to create a visual, experiential journey for viewers in which each element should be connected to the others and each should enhance the experience of the others. My shows are not expressions, opinions or illustrations of reality, but reveal their own truths in the creation of parallel worlds through the arrangement of art objects and artifacts. Individual works stand in specific relationships to each other, both in terms of their physical placement and in terms of their cognitive consonance, dissonance and resonance.

ML: Partners (The Teddy Bear Project) began with a Cattelan taxidermied dog, that wasn’t meant to be art but succeeded as art at complex levels including the aesthetic. What happened with that inspiration, like Jack’s bean that grew to a giant beanstalk?

YH: That’s right, I did not set out to make an artwork, but rather to create a context for Maurizio Cattelan’s taxidermied dog—to make a dead dog look alive. But as a curatorial project, the piece just grew and grew, and took on a life of its own. I showed it first at the Foundation in Toronto, and then as part of Partners at Haus der Kunst in Munich. It was also picked up by other curators—by Kitty Scott and Pierre Théberge for the National Gallery of Canada, and by Massimiliano Gioni for both the Gwangju Biennale and, most recently, the New Museum in New York.

ML: The Milliner’s Daughter is a powerful piece that if done by someone with a different sensibility could have fallen flat like Banksy’s Dismaland. I’m curious about how you’d describe the making of that work, and what statements you’d consider important now for future viewers to consider.

YH: I neither make shows in a vacuum nor to pursue some sociological or even personal agenda. I respond to invitations, creating not only for particular spaces, but also the people who extend the invitations and effectively become working partners. So, The Milliner’s Daughter was made for The Power Plant and Gaëtane Verna, its Director.

To make The Milliner’s Daughter, I started by giving careful consideration to the physical spaces, then selecting or making works to fill them most effectively. I started with the space and constructed a fable for it. The Milliner’s Daughter was conceived and executed as a single work, not the assembly of several pieces curated expressly for The Power Plant.

Some elements in the show, to be sure, had been seen in earlier exhibitions elsewhere, but they “read” in a wholly different way in their placement and configuration at The Power Plant. This is another feature of my practice. The meaning or significance of individual elements are never fixed or unitary. Some of the elements of The Milliner’s Daughter will be part of my upcoming show, Death to Pigs, at the Kunsthalle Wien next spring. In that space, in a new configuration and with new works around them, they will become part of a completely different work. Taking some of the same elements, but adding new installations in a new space makes for an entirely different story.